BY: KATHERINE MELBOURNE, PIP GUEST BLOGGER

When I was eight years old, I decided I wanted to get a doctoral degree. I had just spent some time going through one of my favorite books at the time, Kiss My Math by Danica McKellar, when I noticed that by the author’s name was a suffix I had never seen before: “PhD”. I ran into my parents’ room and asked them what these three little letters meant, listening as my mom explained how they were reserved for very smart people who contributed a unique theory to their field of study.

Wanting to be like the amazing woman who wrote this book, I whipped out my rainbow notepad and sparkly pen and got to work.

After an hour of struggling through my fourth-grade-level arithmetic, the conclusion of my basic calculations showed that 1= 0. Thinking I had broken math and would surely get that coveted “PhD” for my efforts, I tucked the paper with all my mathematical scribbles onto my bookshelf for safekeeping.

Though I didn’t get that doctorate at age eight, I kept that same curiosity and determination through all of my studies. In my imagination, there was no goal too high, no ambition unachievable. Eventually, my interest in science and math led me to discover my love of astronomy. By the time I was in high school, I knew that to become a research professor in astronomy, I would need to understand physics. It wasn’t until my first day in a formal high school physics class, eight years after learning what a PhD was, that I started to doubt my abilities. As one of three female students out of more than 20 in my class, I had my first experience with the gender gap in STEM. Though I was slightly more intimidated by the journey to become an astronomer after that first course ended, I stuck with my original intentions as I graduated high school, went to college, and chose to major in physics.

The introductory STEM courses at most universities are often considered to be the “weed out” courses, designed to separate those truly interested in pursuing a subject from those who are not as serious. Research has demonstrated that this process affects women more than in does men; despite taking similar courses in their K-12 education, significantly fewer women than men graduate from almost every scientific area of study. My freshman year calculus and physics classes hit me hard, and I found myself wondering if I was cut out for STEM as I struggled to grasp the concepts in the most foundational classes our school offered.

Later that year, I became a part of the Women in Physics group on campus. As I began participating more in their events, I realized that those feelings of insecurity and self-doubt had also been felt by many of the female physicists I consider to be role models, including fellow students and professors. Finally, I had found my place as a physics major, both getting and giving support in this community of strong women, who just happened to have a love of science.

Last fall, I realized that my journey in STEM was pushing me in a new direction. As I began thinking about where I would apply for summer research or internships, I found myself searching for opportunities that would allow me to use my physics background indirectly. The idea of advocating for STEM from through public policy was not something I had considered for my own goals before but was something I immediately found interesting. Deciding that pursuing science policy had the potential to completely change my direction in college, I applied to an internship through the Office of International and Interagency Relations at NASA Headquarters for the next internship cycle available over the spring.

“The challenge of being female and a leader in any field does not come from women being any less smart, talented, and capable than their male counterparts. Rather, the challenge comes from not seeing many people like you who have already undertaken the journey you are about to start. ”

Until I spent the last semester off from school to complete this internship in Washington, D.C., my experiences in physics came only through my classes and my research projects. Suddenly, I was involved in science on a governmental scale. My focus shifted from depth to breadth; instead of contributing to one project, I had an impact on many projects as I helped draft agreements with foreign partners and plan international seminars. I supported work in aeronautics, astrophysics, and everywhere in between, learning pieces about each program mission along the way. Immersed in my work at NASA, I realized that I don’t have to be in a lab to support my interests in science and to advocate for women in STEM. Work happening through the government to ensure the success of individual projects in STEM is just as essential as the work of scientists to push their fields forward.

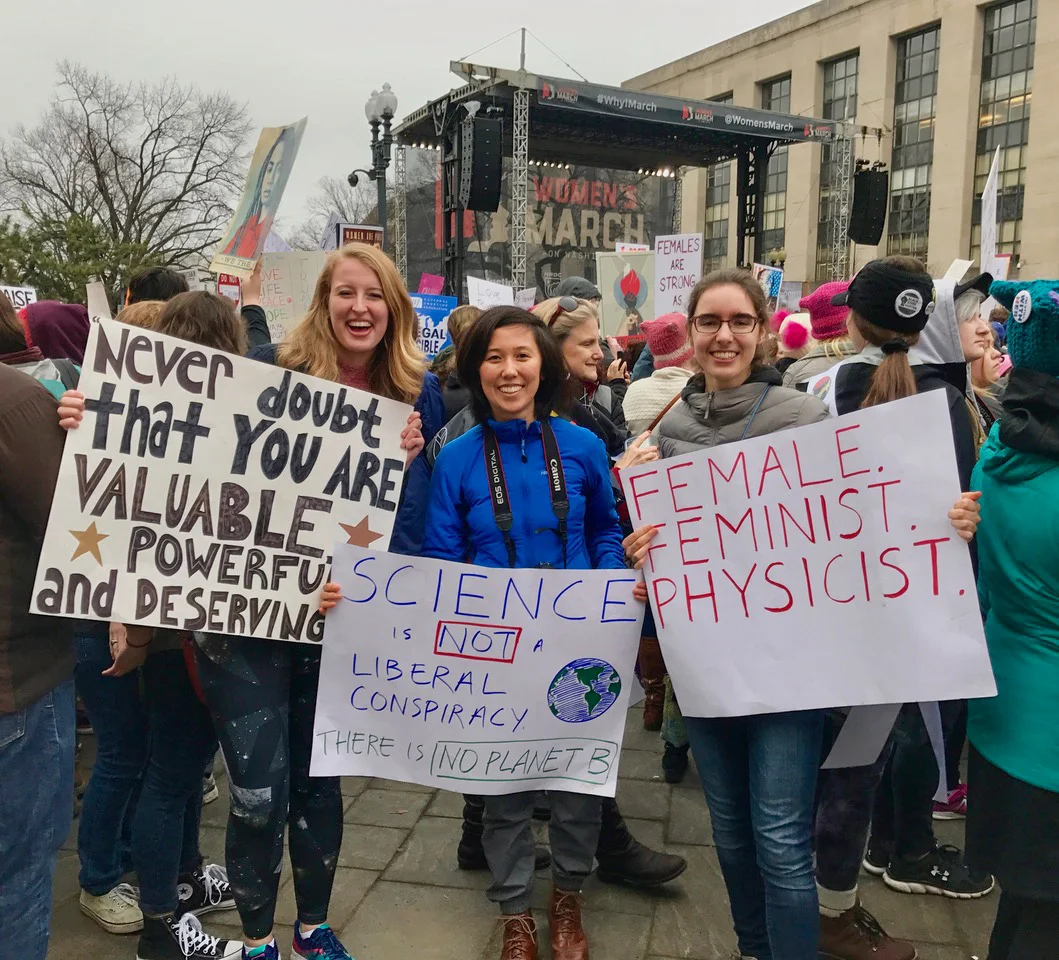

As I continue to study physics while branching out to explore science policy, I’ve realized that the challenge of being female and a leader in any field does not come from women being any less smart, talented, and capable than their male counterparts. Rather, the challenge comes from not seeing many people like you who have already undertaken the journey you are about to start. Any female leader is inherently an innovator, paving the way for others to follow and making it easier for others to create their own paths in the future. It is this idea that keeps pushing me forward. Although my future goals might change, I now can reassure my eight-year-old self, knowing that women can do anything, especially when we empower those around us along the way.

Katie is from Bettendorf, Iowa and is a sophomore Physics major at Yale University. With a combined interest in scientific research and communication, she intends to pursue a career working toward the advancement of science through policy development and public education. She is on the board of the Yale Women in Physics, and outside of STEM, she loves to plays clarinet in the marching band and train for half-marathons.