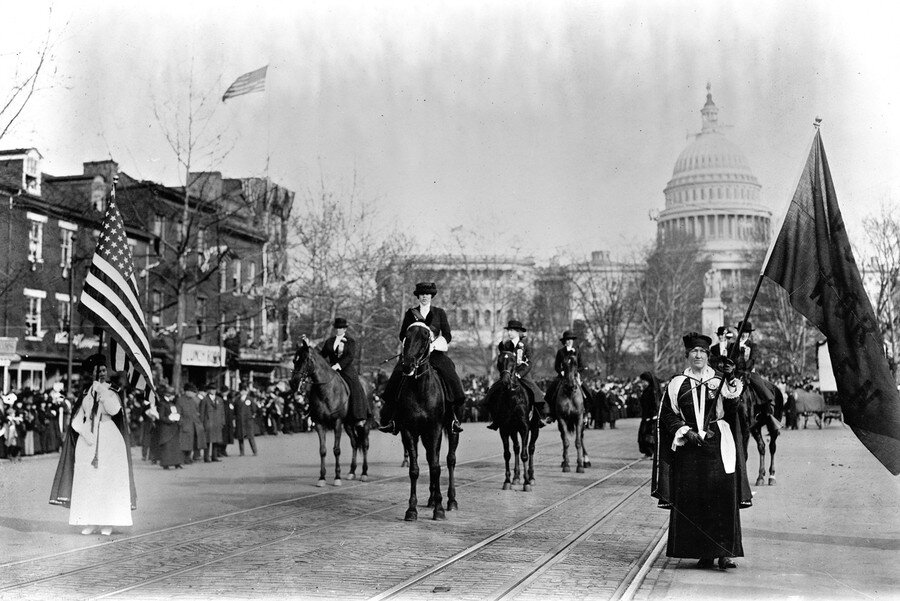

Photo Courtesy of Brit + Co

By: Sophia Walker, Summer 2021 Collaborator at Power in Place

A question often raised regarding women in politics is: why don’t more women run for office? Or, they can run, so why don't they? While these questions are fundamental to ask, they don’t capture the whole picture of politics and women. Women are continuing to increase their representation in politics, but there are still barriers that work against them. The obstacles they face are societal in some cases and physical in others.

The most prominent societal barrier is patriarchy. In essence, the patriarchy labels men as better even if they have the same qualifications as a woman. Women are seen as less experienced or of lesser quality because of this view. On a day-to-day basis, that perception gets highlighted in different realms. When it comes to politics, it will deter women from running [5]. While men might receive articles on their policy, women are likely to be subject to scrutiny. That may come in the form of questioning policy choices or decisions but is more likely focused on fashion choices or a new haircut. The trivial things women get placed under a microscope for are never brought up concerning men [4]. A man does not have to worry about being labeled too emotional or rude based on tone. The barrier of patriarchy continues to make women think twice about running. They have to consider if they want to be perceived that way in the media—hindrance men do not have to consider.

In addition, women still don’t receive the same educational opportunities. It may seem that when girls and boys go to school, they are in the same classes. While they might physically be in the same room, teachers often undervalue the abilities of female students compared to male students. That occurrence gets heightened further when it comes to mathematics or other STEM subjects [3]. Education inequality is apparent in younger children but also in higher education. Women often are told which majors they will or will not succeed at based on their gender [1]. The unequal opportunity of education affects women in politics by making them feel that they do not belong in that educational realm.

Another factor affecting women when deciding to run is the lack of respect for caregiving in our society. Women often take care of children, a family member, or a spouse while having another job. Caregiving often takes the same amount of energy and time as a job, doubling the workload [5]. While a man does not typically have the same quantity of responsibilities, women are instantly a step behind a man. In politics, women can receive shame for taking time off to stay at home or taking care of a parent. Those factors combine to make a woman less likely to run because of these additional responsibilities.

Specifically to children, women with a career get perceived as trying to have it all. Or, a woman who takes time off to be with a child will get designated as someone who doesn’t care about her job. In politics, a woman running may be shown as not giving her children enough attention. Whether on the campaign trail or while in office, women face the double standard of being a mom and having a career. The view on children and having a career makes women think again about if running is a good decision for them.

The blocks described are common to all women but are detrimental to getting more women into politics. While the situation might seem bleak and the barriers insurmountable, current women representatives continue to show that the barriers are not a reason to stop fighting. One prime example comes from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. When her male counterparts commented on her, using derogatory terms and sexism, she took that moment to stand up for herself. She not only mentioned that incident but the roadblocks many women face [2]. While just one example, women representatives are continuing to make their voices heard more than ever before. With more women representative role models in place, I hope more women begin to run for office.

Boschma, Janie, and Ellen Weinstein. “Why Women Don't Run for Office.” POLITICO, Politico, 12 June 2017, www.politico.com/interactives/2017/women-rule-politics-graphic/.

Broadwater, Luke, and Catie Edmondson. “A.O.C. Unleashes a Viral Condemnation of Sexism in Congress.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 24 July 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/07/23/us/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-sexism-congress.html.

Cimpian, Joseph. “How Our Education System Undermines Gender Equity.” Brookings, Brookings Institute, 23 Apr. 2018, www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/04/23/how-our-education-system-undermines-gender-equity/.

McGregor, Jena. “Why More Women Don't Run for Office.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 23 Apr. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/news/on-leadership/wp/2014/05/21/why-more-women-dont-run-for-office/.

White, Jeremy B., et al. “What Are the Biggest Problems Women Face Today?” POLITICO Magazine, Politico Magazine, 8 Mar. 2019, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/03/08/women-biggest-problems-international-womens-day-225698/.

Sophia Walker is a rising senior at Drake University. She is a double major in Law, Politics and Society and Sociology with a minor in Marketing. Sophia has a passion for social justice and women’s rights. On campus, Sophia is part of the Drake Dems and the Roosevelt Institute. She is also a CASA volunteer in her free time.